‘Your GP is 4 minutes away…’

I was at a GP conference recently where I got talking to one of the exhibitors. They were promoting an app that allows patients to request a GP consultation at home or the location of their choice at any time, much like ordering an Uber taxi. The GP just has to sign in to show they are available and patients can book away!

I had lots of questions for them and it got me thinking about online healthcare in general.

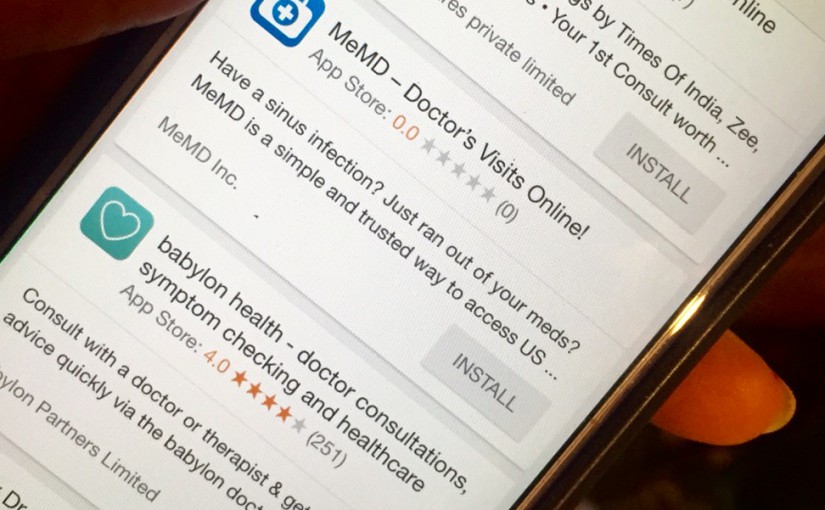

So what is online healthcare? I A brief Google search for ‘online healthcare’ revealed plenty of sites offering healthcare services delivered through email, apps and telemedicine, with some providers charging in excess of £100 per consultation. The demand for digital healthcare is clear: the UK market is worth £2 billion. It would be interesting to see just how many people have accessed e-health providers over recent years and gage their support for or against the privatization of the NHS.

However this form of healthcare has obvious pros and cons.

Online healthcare would no doubt be a flexible and lucrative way of working for many GPs with no commitment to a fixed number of sessions. Recruitment of GPs to private online companies, however, raises concerns about an already depleted NHS workforce, one that we are fighting to retain.

Sharing the workload with digital health providers could reduce the burden on NHS services and meet patient demand for quick and convenient access to a doctor, which is something general practice has struggled to achieve in recent years. With plans for a 7-day service looming, could e-health be the answer?

Patients would be able to have longer appointments with a doctor and get medications delivered to them, which would be of particular use to those that find it difficult getting to their GP surgery. It could potentially even take the pressure off out of hours care providers as patients could be seen at their workplace during the day.

Some would argue that in this day and age healthcare shouldn’t be stuck in the stone ages and embracing these new innovations can only be a positive step.

So, what are the pitfalls?

Part of the public health focus in the UK is reducing health inequalities by making sure everyone has equal access to healthcare. The increase of digital providers benefits those who can afford these premium services, but for many it is not an option. The ease of accessing GPs via apps or websites could devalue the profession and leave it open to abuse – people cancelling last minute, inappropriate requests and questionable safety of doctors visiting people at unconventional locations.

Seeing people in a GP practice confers a level of safety for both doctor and patient. Home visits are often reserved for patients who are frail, acutely unwell or those with chronic illnesses who have established a trusting relationship with a GP.

We must also consider the privacy and security of a patient’s personal data. Will the information be transmitted using proper encryption and is access to medical records protected so only those who have a right to see it do?

Many of the sites do not offer care to children which means parents will still have to access their local GP for help. With children we are inherently more cautious and face-to-face consultations are recommended in most cases to practice safely.

Private providers may not have access to a patient’s medical records such as their drug history, which results in a lack of safe drug monitoring and incomplete past medical history if the patient in unable to tell the visiting GP.

Continuity is lost if a patient is seen in different care settings, which could give rise to an inaccurate picture of that person’s health. A lot of our work as GPs is to tackle problems that a patient frequently presents with and to help them decipher what the root cause might be. These opportunities could be lost which is disappointing for someone who like me who is keen for the implementation of unified medical records for each patient.

In the case of telephone and video consultations, the presenting problem may not be something that can be dealt with from a distance, thus generating a referral to the patient’s GP, walk-in services or secondary care and therefore increasing NHS workload.

The prime minister’s challenge fund was set up in October 2013 to improve access to GPs and to adopt innovative ways of providing various services. The pilot included 1,100 GP practices, providing care to 7.5 million patients. Two years after its inception, a progress report showed that 6 of the 20 pilot sites had introduced online diagnostic and/or video consultations. 6 pilot sites had also trialled GP e-consultations. This had a mixed reception from both GPs and patients.

There is still a way to go in ensuring the ethical and safety concerns of online healthcare providers are addressed and it may be that GP practices should take the lead in providing safe digital services if provided with adequate training, funding and staffing.

Dr Aisha Yahaya